Metastatic melanoma with unknown primary site (MUP) is a rare disease and represents about 2-9% of all melanomas. Melanoma is a type of skin cancer that forms in the pigment-producing cells of any part of the body like skin, mucosa, eye and rarely other sites. The spread occurs through the lymphatic system and/or the blood vessels. The author hereby reports the case of a middle-aged woman with a sudden swelling of the right inguinal crural region, painless and progressively increasing, which was later found to be a metastatic malignant melanoma of the inguinal lymph nodes, with no clinical or radiological evidence of a known primary lesion.

More than 97% of all melanomas are diagnosed with a known primary site, most often involving the skin (1-2). Less commonly, melanoma can present within the eye or mucous membranes [1]. Rarely, melanoma is diagnosed without an obvious primary site, and is referred to as melanoma of unknown primary (MUP). In 1963, Das Gupta originally defined MUP as melanoma discovered in subcutaneous tissue, lymph nodes (LNs), or visceral organs without a cutaneous, ocular, or mucosal primary site [2]. Metastatic melanoma with unknown primary melanoma (MUP) is characterized by the presence of melanoma metastases in the lymph nodes, subcutaneous tissue or visceral sites in the absence of evidence of primary tumor despite detailed skin examination and multiple complementary examinations in each site of the body [3]. Melanoma commonly metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, liver, lungs, bones or brain, spreading through lymphatic and haematogenic pathways. It may also metastasize to the skin, both locally and at distant sites [4]. For classification purposes, MUP can be subcutaneous, nodal and visceral, with nodal MUP as the most common. Here the author describes the case of a 52-year-old woman diagnosed with melanoma metastasis in the right inguinal-crural site after excision of a lymph node with suspected neoplastic disease features.

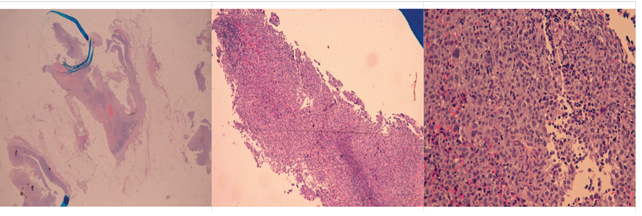

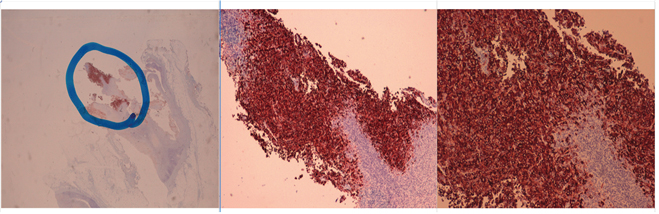

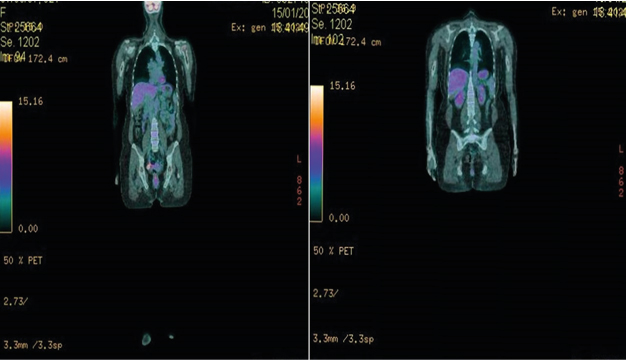

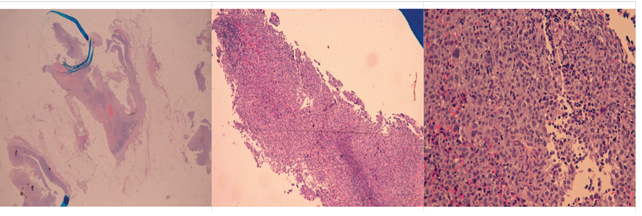

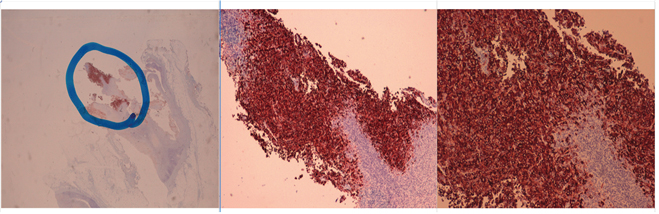

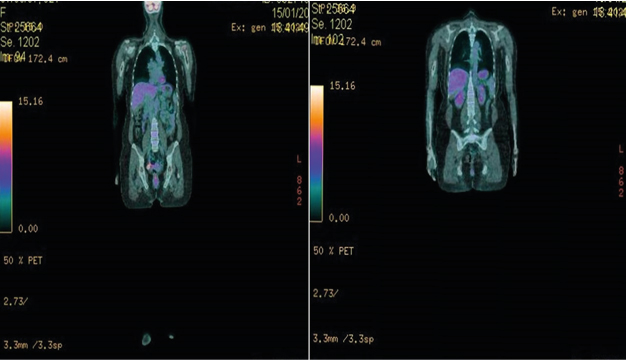

A 52-year-old woman, apparently in good health, came to her general practitioner's office complaining of a painless swelling in her right groin. Her family history and medical history were negative and there were no recent febrile symptoms or illness. In 2010 the patient underwent surgery to remove an alleged left arm neurinoma. A recent dermatological examination was negative for epithelial lesions with absence of suspected nevi. A gynecological examination was also negative. Laboratory tests were normal. The objective examination showed a hard, non-painful swelling of the underlying tissues in the right crural groin. There were no appreciable lymph nodes in other sites. An ultrasound of the many superficial tissues confirmed the presence of an uncertain lymph node packet in the same site. As a result, the patient underwent excisional biopsy of the lymph node that was positive for melanoma metastasis Figure. 1 - Figure. 1 bis, in the absence of a known primary lesion. As a result, a total body Tomoscintigraphy scan (Fig. 2) was required to detect capturing lesions in order to assess other sites of disease and it was proposed to search for the BRAF mutation. At the end, the patient underwent excision of the tumour mass with complete inguinal lymph node dissection. After surgery, radiotherapy and immunotherapy were done.

Legends Figure 1 and Figure 1bis Showing the Histological Specimens of Linfonodal Metastatic Melanoma. The Images Were Both Recorded With Hematoxylin Eosin (EE) In Panoramic (2.5x) and In 2 Different Magnifications (5x and 10x) and the Same Shots With Immunohistochemical Staining MART-1 Which Demonstrates The Nature of Neoplastic Cells

Figure 2: Shows the Total Body Tomoscintigraphy Images without Signs of the Primary Tumor

MUP, whose origin is not yet fully understood, represents about 2-9% of cases of metastatic melanoma [5]. The average age of patients presenting with MUP is in the fifth and sixth decade of life [6]. It occurs more commonly in men than in women, although this is currently unexplained. It is thought that the primary tumour cells of the primary lesion may have regressed due to lymphocytic activity. In fact, regression in melanoma is well documented, with a frequency of up to 10%. In addition, the primary skin lesion may have been removed or otherwise destroyed without adequate histological analysis. Furthermore, the primary melanoma may have been misinterpreted as a benign nevus based on clinical and non-pathological features. Finally, the malignant transformation of ectopic melanocytes into lymph nodes or other organs may have occurred de novo [3, 7]. MUP mutations include mutations in the BRAF genes (in particular subtype V600E) and NRAS [8]. This data considers the theory that MUP represents metastases from an original primary skin melanoma that may or may not have spontaneously regressed. As the primary site of the melanoma is unknown, the presentation of MUP is atypical, in that there is no clinically apparent primary cutaneous lesion. Rarely, the primary melanoma is later found at an extra cutaneous site, such as in the eye, or in a sinonasal, vulvovaginal, or gastrointestinal area. In most cases, the primary melanoma cannot be found [8]. The most common clinical presentation of MUP is lymph node disease without clinical or radiological evidence of visceral involvement. Lymph node metastases commonly arise in the axillary (50%), neck (26%), and groin (20%) lymph nodes [3]. In cases of MUP spreading to visceral sites, the initial symptoms are site-specific. Hepatic melanoma may present with hepatomegaly, jaundice, or an abdominal mass. Pulmonary melanoma can include a pulmonary lesion or pleural effusion. Advanced MUP that has spread to distant sites may also present with systemic features related to cytokine production, such as fever, weight loss, and anaemia [9]. How is metastatic melanoma with unknown primary lesion diagnosed? The diagnosis of MUP is usually made based on clinical signs and symptoms consistent with metastatic disease, along with histopathology of a tissue specimen that confirms the presence of malignant melanocytes, such as excisional biopsy of the lymph node or needle core biopsy of a solid organ metastasis [10]. The histological features of MUP on a tissue specimen include: The presence of the brown pigment melanin-this is not present in amelanotic melanoma. Positive melanocytic immuno histochemical markers, such as S100, Melan-A, HMB-45 and SOX10 (SOX10 has been shown to be a reliable marker for identifying metastatic melanoma) [10, 11]. It is currently not possible to predict the primary site of MUP from histology, immunohistochemistry, or genetics [10, 11, and 12]. Fortunately, the prognosis for this type of patient is better than for patients with known primary lesion and metastatic disease [13].

Metastatic melanoma could theoretically develop synchronously with a subclinical or otherwise unrecognized cutaneous, ocular, or mucosal melanoma. This is a less likely explanation for MUP if follow-up times are adequate, however, because the known primary will likely declare itself by the time metastatic disease has developed. The predominant hypothesis for MUP involves the spontaneous regression of melanoma from a known primary site. Malignant melanoma with unknown primary lesions is a very rare clinical entity but should be known by physicians and therefore considered in the differential diagnosis of all patients with lymphadenopathy of uncertain significance and suspected of malignancy even in the absence of an unknown primary lesion. Since these types of stage III malignancies have a better prognosis than similar tumors with a known primary site (i.e. stage IV), aggressive management with a complete loco regional lymphadenectomy followed by adjuvant chemotherapy-radiotherapy and/or immunotherapy is justified.

None to disclosure

The author would like to thank Dr. Giovanni De Luca of the Dept. of Pathology - Ausl Della Romagna (Head Dr. Daniela Bartolini) for his courtesy to give the histology specimens of metastatic melanoma, and dr. Michela Casi (Head of the Nuclear Medicine Dept.) for the Tomoscintigraphy images

- Chang AE, Karnell LH, Menck HR (1998) The National Cancer Data Base report on cutaneous and noncutaneous melanoma: A summary of 84, 836 cases from the past decade. The American College of Surgeons Commission on Cancer and the American Cancer Society. Cancer 83: 1664-1678. [Crossref]

- Dasgupta T, Bowden L, Berg JW (1963) Malignant melanoma of unknown primary origin. Surg Gynecol Obstet 117: 341-345. [Crossref]

- Van Beek EJAH, Balm AJM, Nieweg OE, et al (2015) Treatment of regional metastatic melanoma of unknown primary origin. Cancers (Basel) 7: 1543-1553. [Crossref]

- Situm M, Buljan M, Kolic M, et al. (2014) Melanoma-clinical dermatoscopical and histopathological morphological characteristics. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat 22: 1-12. [Crossref]

- Pfeil AF, Leiter U, Buettner PG, et al (2011) Melanoma of unknown primary is correctly classified by the AJCC melanoma classification from 2009. Melanoma Res 21: 228-234. [Crossref]

- Tos T, Klyver H, Drzewiecki KT (2011) Extensive screening for primary tumor is redundant in melanoma of unknown primary. J Surg Oncol 104: 724-727 [Crossref]

- Kibbi N, Kluger H, Choi JN (2016) Melanoma: clinical presentations. In: Kaufman HL Mehnert JM (Eds) Melanoma. Switzerland: Springer 107-129. [Crossref]

- Egberts F, Bergner I, Kruger S, et al (2014) Metastatic melanoma of unknown primary resembles the genotype of cutaneous melanomas. Ann Oncol 25: 246-250. [Crossref]

- Kamposioras K, Pentheroudakis G, Pectasides D, et al (2011) Malignant melanoma of unknown primary site. To make the long story short. A systematic review of the literature. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 78: 112-126. [Crossref]

- Oien KA (2009) Pathologic evaluation of unknown primary cancer. Semin Oncol 36: 8-37. [Crossref]

- Bae JM, Choi YY, Kim DS, et al (2015) Metastatic melanomas of unknown primary show better prognosis than those of known primary: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Acad Dermatol 72: 59-70. [Crossref]

- Neuman HB, Patel A, Ishill N, et al (2008) A single-institution validation of the AJCC staging system for stage IV melanoma. Ann Surg Oncol 15: 2034-2041. [Crossref]

- Van der Ploeg AP, Haydu LE, et al (2014) Melanoma patients with an unknown primary tumor site has a better outcome than those with a known primary following therapeutic lymph node dissection for macroscopic (clinically palpable) nodal disease. Ann Surg Oncol 21: 3108-3116. [Crossref]