Background: Brucellosis is the most common zoonotic infection worldwide. The infection is caused by the bacterial genus Brucella. It is transmitted from animals by consumption of unpasteurized milk or milk products, or by direct contact with infected livestock. In countries of high prevalence, such as in Saudi Arabia, brucellosis continues to be of public health and economic significance. Brucellosis is a multisystem disease and infected persons may present with a wide spectrum of manifestations. The most common feature of systemic brucellosis in humans is fever, followed by myalgia and arthralgia, sweating, and constitutional symptoms.

Case: We report a young patient presenting with post stroke epilepsy secondary to Neurobrucellosis infection

Conclusion: Neurological symptoms and stroke of undetermined etiology in patients living in an endemic area should prompt testing for brucellosis.

Neurology; Neurovascular; Neuro-Infectious; Epilepsy

Human brucellosis remains endemic in the Mediterranean basin, Middle East, Western Asia, Africa, and South America. The disease is mainly transmitted to humans through the ingestion of raw milk or non-pasteurized cheese contaminated with Brucella species pathogenic to humans [1]. Neurobrucellosis is an uncommon complication of systemic brucellosis. Neurological involvement occurs in 2 to 7 percent of cases [1-3]. Manifestations include meningitis (acute or chronic), encephalitis, myelitis, radiculitis, and/or neuritis (with involvement of cranial or peripheral nerves) [2, 4].

This report highlights the evolution of symptoms in a young patient, previously medically free. His history started 1 year before his visit to our hospital when he experienced a sudden onset of word finding difficulty, for both simple and complex words, that was persistent for 2 months then subsided by itself which he didn’t seek any medical advice for.

Two months after, the patient had an episode of auditory hallucinations (hearing voices inside his head) followed by dystonic posturing of his right arm that progressed to generalized tonic clonic seizure for 1-2 minutes. There was no headache, fever, oral ulcers, rashes or hair loss, no history of trauma, nor any other systemic involvement.

He was started on Levetiracetam 500 mg twice a day (BID) in his local hospital and referred to our hospital for investigation of stroke in young after brain CT showing left temporo-parital ischemic insult.

Up on his arrival to our clinic he was hemodynamically stable with normal general and neurological exam including cognitive testing.

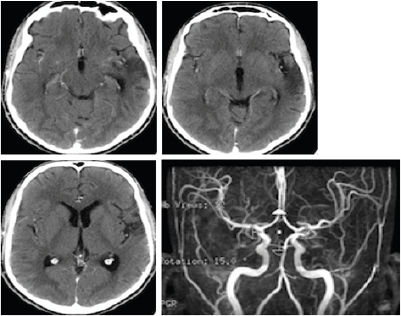

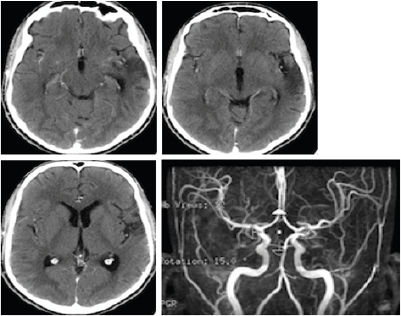

Routine investigations including CBC, renal profile, hepatic profile, and bone profile were normal. CT/CTA brain were done and showed focal area of subacute ischemic insult in the left parietal operculum extending into periventricular white matter of left temporal lobe and beading appearance of the distal branches of left MCA (M3 branches). (Figure 1)

Figure 1:

Brucella titers and Brucella total antibodies from serum were 1:20480 and IgG antibodies of 1:20480, CSF serology showed Brucella total antibodies 1:20480 and IgG antibodies 1:2560 with positive Brucella culture in CSF.

The patient was started on oral Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice a day (BID), Rifampin 600 mg daily (OD), Bactrim 160 mg twice a day (BID) for 9 months, and intramuscular (IM) Streptomycin 1 gm Daily for 2 weeks. And he was kept on Levetiracetam 500 mg twice a day (BID).

Brucellosis is the most common zoonotic infection worldwide. The infection is caused by the bacterial genus Brucella. It is transmitted from animals by consumption of unpasteurized milk or milk products, or by direct contact with infected livestock and more than 500,000 new cases occur annually [3, 4]. It has a global distribution, but occurs more commonly in countries where domestic animal health is not standardized. A high incidence of disease has been reported in Mediterranean and Middle Eastern countries [4]. In countries of high prevalence, such as in Saudi Arabia, brucellosis continues to be of public health and economic significance [5]. Brucellosis is a multisystem disease and infected persons may present with a wide spectrum of manifestations [6]. The most common feature of systemic brucellosis in humans is fever, followed by myalgia and arthralgia, sweating, and constitutional symptoms [1, 4].

Neurobrucellosis, although uncommonly occurs only in 2-7% of cases, is a serious complication of brucellosis, and can present in any stage of the disease [1-3]. The mechanism by which brucellosis leads to nervous system involvement can be explained by either of 2 mechanisms: Persistent intracellular microorganism or due to an immune mechanism triggered by the infection [4]. Neurobrucellosis presents with heterogeneous clinical manifestations that lead to discrepancies in the diagnosis [3, 4]. The course of the disease has been reported to be chronic, and its symptoms present insidiously [1]. The neurological involvement of brucellosis can be divided into 3 categories: Meningoencephalitis, polyradiculopathy, and diffuse involvement. It may also present with psychiatric symptoms, such as depression, hallucination, or personality disorder [2, 4].

Cerebrovascular accidents due to brucellosis manifest due to 2 mechanisms. First, hemorrhage which may result from rupture of a mycotic aneurysm. The second mechanism is vasculitis leading to infarcts, small hemorrhages, or venous thrombosis [4]. Neurobrucellosis mimicking cerebrovascular accidents has already been reported in the literature; however, because brucellosis is not amongst the common causes of stroke, it is still not investigated for in patients who present with a stroke. The pooled review study done by Hanefi et al in Turkey, which is one of the endemic countries for brucellosis, reported stroke to be one of the least common complications, with only 3.2% of the patients developing it [6]. Four of the reported cases were caused by ischemia, 1 was subarachnoid hemorrhage, and 1 was a subdural hematoma. The age of the patients evaluated in the study was not mentioned.

In another study done in Saudi Arabia by Alsous et al only one patient out of 23 had lacunar stroke with small hypothalamic hemorrhage and perivascular enhancement with complete recovery after 9 months of treatment [7].

In areas where brucellosis is endemic, Neurobrucellosis should be considered for each young patient presenting with unexplained stroke [4].

In the literature, the diagnostic criteria for Neurobrucellosis are still controversial. The diagnosis of Neurobrucellosis is sometimes based on symptoms, whereas some other authors base it on microbiological evidence from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [6]. The diagnostic criteria require one of the following: (1) The presence of neurological symptoms in patients with brucellosis; (2) isolation of Brucella species of the cerebrospinal fluid and/or presence of anti-Brucella antibodies in the CSF; (3) the presence of lymphocytosis, increased protein, and decreased glucose levels in CSF; or (4) diagnostic findings in cranial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT) [1, 6]. In most cases, the diagnosis of Neurobrucellosis is only made 2-12 months after the onset of symptoms. Thus, a delay in treatment may lead to an increase rate of mortality [6].

The gold standard test for the diagnosis of Neurobrucellosis is culture of the cerebrospinal fluid. The sensitivity of tube agglutination in cerebrospinal fluid is noted to be 0.94, the specificity is 0.96, the positive predictive value is 0.94, and the negative predictive value is 0.96 [6]. However, it is not commonly done because of the slow growth rate of the microorganism causing this method to be time consuming. Another disadvantage is the low isolation rate of Brucella species from CSF. The low growth rate may be due to the use of antibiotics before the referral to a tertiary-care hospital [1, 2, 6]. In a study by Guven et al, of the 128 patients with brucellosis confirmed by laboratory, 37.5% were diagnosed with Neurobrucellosis, and Brucella bacteria was isolated from the CSF in only 15% of patients [6]. In other study conducted in Turkey, the isolation of Brucella species ranged from 15-30% [2].

In most practices, the agglutination titer for the detection of specific antibodies in CSF is used for the diagnosis of Neurobrucellosis. The titer is counted using either trans-agglutination test or enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA). Although ELISA test is fast and accurate, the diagnostic performance of the 2 tests was found to be similar [2, 6]. There is no consensus on the acceptable amount of titer in CSF to be used in the diagnosis of Neurobrucellosis.

Neurological symptoms and stroke of undetermined etiology in patients living in an endemic area should prompt testing for brucellosis.

- Khademi A, Poursadeghfard M, Noubar RN (2016) Neurobrucellosis Presented with A Hyperacute Onset: A Case Report. Iran J Public Health 45: 1652-1655. [Crossref]

- Karsen H, Koruk ST, Duygu F, et al. (2012) Review of 17 Cases of Neurobrucellosis: Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management. Archives of Iranian Medicine 15: 491-494. [Crossref]

- Zheng N, Wang W, Zhang JT, et al. (2017) Neurobrucellosis. Int J Neurosci 24: 1-8. [Crossref]

- Gul HC, Erdem H, Bek S (2009) Overview of Neurobrucellosis: a pooled analysis of 187 cases. Int J Infect Di 13: 339-343. [Crossref]

- Al-Sekait MA (2000) Epidemiology of brucellosis in al medina region, Saudi Arabia. J Family Community Med 7: 47-53. [Crossref]

- Guven T, Ugurlu K, Ergonul O, et al. (2013) Neurobrucellosis: Clinical and Diagnostic Features. Clinical

- Infectious Diseases 56: 1407-1412. [Crossref]

- Alsous MW (2004) Neurobrucellosis clinical and radiological correlation. AJNR Am J Neuroradiology 25: 395-401. [Crossref]