Lung cancer is the most common primary malignancy, with typical sites of metastasis including the liver, brain, bone, and adrenal glands. Reports of metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract are uncommon, ranging from 0.2-0.5%, but higher rates are seen in autopsy reports at up to 1.8%. Since gastrointestinal (GI) symptoms may be misattributed to treatment side effects, GI track metastases can be missed clinically. Here we report a case of metastatic non-small cell lung cancer to the sigmoid colon and discuss the presenting symptoms, diagnostic work-up, and imaging and pathology findings.

Case: We report a case of non-small cell lung cancer metastasis to the sigmoid colon.

Conclusion: Lung cancer patients presenting with GI obstruction or other new or worsening abdominal symptoms may warrant a search for GI tract metastasis secondary to primary lung tumor, which is clinically underdiagnosed and signals poor prognosis.

Metastatic NSCLC; Lung Adenocarcinoma; Sigmoid Colon; CK7; CK20; Napsin A; TTF-1

Lung cancer remains the leading cause of cancer-related deaths [1-3]. Common lung cancer metastasis sites include liver, brain, bone, and the adrenal glands.3,4 Here, we report an uncommon case of primary non-small cell lung cancer metastasis to the sigmoid colon. We then review the literature regarding incidence, clinical presentation, relevant imaging findings, and pathology findings.

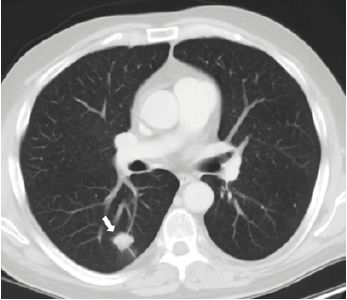

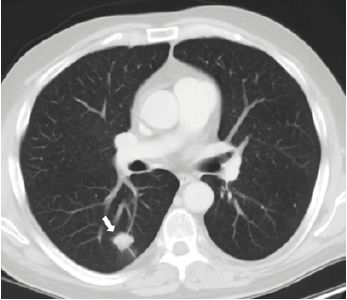

A 62-year-old male undergoing treatment for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) presented to clinic complaining of worsening oral intake, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain for the past two weeks. Two years ago, the patient had been diagnosed with pT1b pN0 M0 stage IA2 lung cancer, with a spiculated nodule in the right lower lobe (figure 1) treated with right lower lobectomy.

Figure 1. Contrast-enhanced axial ct chest shows the primary malignancy in the right lower lobe as a 1.9 x 1.7 x 1.3 cm solid spiculated lung nodule

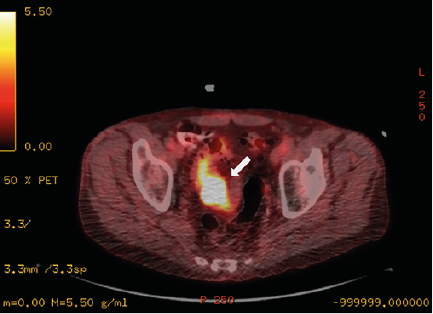

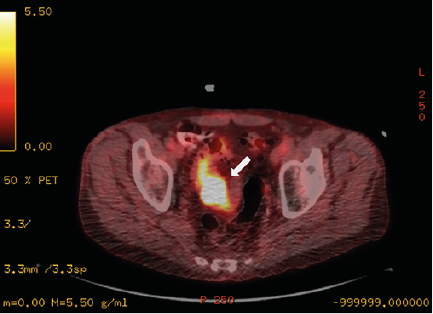

He subsequently developed metastases to the spine, ribs, pelvis, and thigh and was undergoing chemotherapy and palliative radiation. On surveillance CT imaging, he was noted to have an area of thickening of the sigmoid colon which was hypermetabolic on FDG-PET (figure 2). The mass had also grown in size for 2 years, however, was biopsy-proven to be nonmalignant. The decision was made to start palliative radiation treatment to the pelvis 1 week prior to the patient’s presentation since the mass had continued to grow.

Figure 2. Axial PET-CT Fused Image of the Pelvis Demonstrates Persistent Activity at the Sigmoid Colon with a Standardized Uptake Value (SUV)-max of 23, Increased from an SUV-max of 16.3 Several Months Prior

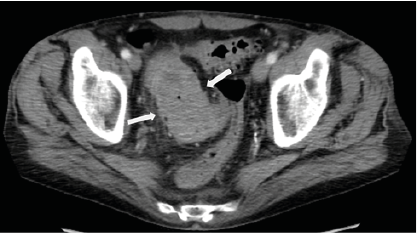

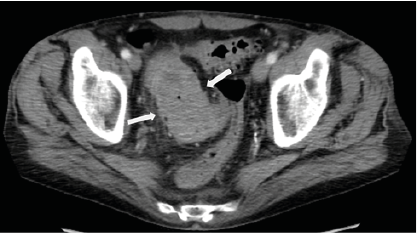

Given the patient’s new symptoms, he was directed to the emergency department with concern for acute colonic obstruction. Physical exam demonstrated diffuse abdominal tenderness with voluntary guarding. His hemoglobin was reduced to 10.2 g/dl from a baseline of 12.5 g/dl two months before, and CEA level was elevated at 269 ng/ml. The most recent outpatient contrast-enhanced CT abdomen and pelvis study had identified the 7.0 x 4.0 cm mass in the distal sigmoid, increased from prior when it measured 6.1 x 3.3 cm, with new pericolonic fat stranding which was interpreted as secondary to radiation colitis (figure 3).

Figure 3. Contrast-Enhanced Axial CT Pelvis Around the Time of Presentation to the Emergency Room Demonstrates A Near-Obstructing Sigmoid Mass, Measuring 7.0 x 4.0 cm with Associated Pericolonic Fat Stranding and Colonic Wall Thickening

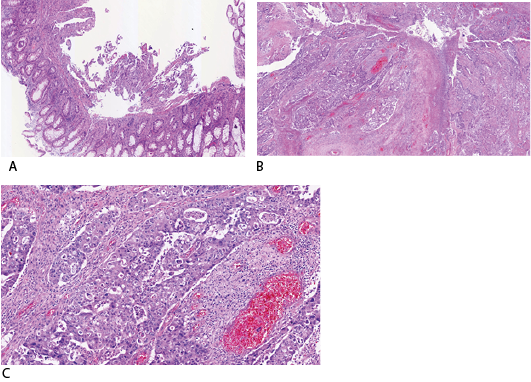

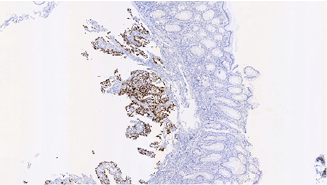

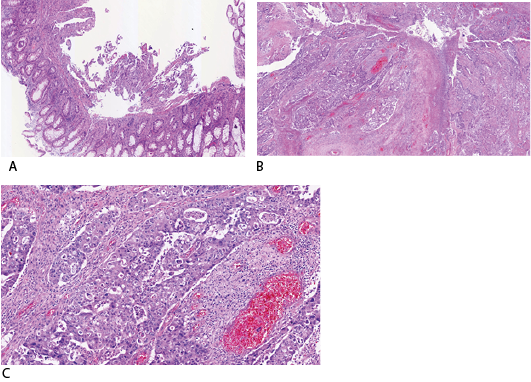

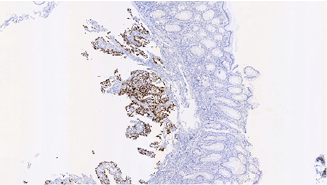

The patient was admitted and underwent an inpatient flexible sigmoidoscopy, revealing an ulcerating, fungating, near-obstructing circumferential mass 20 cm proximal to the anus. The patient subsequently underwent a low anterior resection with end colostomy creation. Pathology revealed a red-tan solid, slightly hemorrhagic, partially obstructing mass at the distal sigmoid with 2.2 cm invasion through the muscularis propria. The tumor demonstrated sheets of infiltrative cells with pleomorphic nuclei within the colonic mucosa compatible with poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma (figure 4a-c). The immunohistochemical staining demonstrated TTF1(+), CK7(+), Napsin A (+), CDX2(-), CK20(-) (figure 5). The post-operative course was uneventful, and the patient continued to undergo palliative treatment.

Figure 4a-c Hematoxylin and Eosin Stained Samples in Various Magnifications from the Resected Colon Show Sheets of Large Infiltrative Cells with Pleomorphic Nuclei within the Colonic Mucosa Compatible with Poorly Differentiated Adenocarcinoma.

Figure 5. Positive TTF-1 Immunohistochemical Staining of the Resected Sigmoid Colon Indicates a Lung Primary Adenocarcinoma Rather Than A Primary GI Tumor.

Epidemiology and Clinical Presentation

Lung cancer is the most common cancer in the United States, comprising over 25% of all cancer deaths [1-3]. The most common sites of metastasis for primary lung cancer are liver, adrenal glands, bone, and brain [3, 4]. By contrast, metastasis to the gastrointestinal tract is often clinically undetected, and more commonly diagnosed in post-mortem exams [4-6]. One report of 423 lung cancer autopsies over a 36 year period indicated that up to 14% of patients with primary lung cancer had developed metastases to the GI tract, with the most common site being the esophagus, but close to half of those metastases were from direct extension.6 Excluding the esophagus, the most common metastasis site was the small bowel, followed by the colon.6 Studies reporting the rate of lung cancer patient autopsies found to have GI metastases (excluding the esophagus) range from 0.1 - 1.8 %.7,8 A separate study of 366 cases of gastrointestinal metastasis found that the most common complications were perforation (42%), followed equally by hemorrhage or obstruction.9 The mean survival time from published studies are low, ranging from 1.6 to 2.8 months [7-9].

Routine surveillance after completion of therapy for lung cancer includes clinical evaluation and interval chest CTs. However, new constitutional symptoms, such as changes in eating habits, abdominal pain, constipation, and hematochezia, warrant further imaging as they may be signs of distal metastasis [9]. More serious manifestations of GI metastases include ileus, intussusception, and perforation. During chemoradiation, these symptoms may be conflated with treatment-associated side effects, such as enterocolitis, radiation enteritis, or ulcer formation, rather than disease progression [10]. Thus clinical suspicion must be high during and after treatment to perform further workup, such as CT, PET/CT and endoscopy [11].

Radiographic findings of colonic tumor include wall thickening or a polypoid or exophytic mass. Patterns of contrast enhancement are variable, and since colonic tumors frequently show isoattenuation, PET-CT is useful in identifying focal areas of increased tracer uptake in the GI tract [12-14]. Colonoscopy is then used to characterize the lesion by describing the degree of obstruction and ulceration, measuring the distance from the anal verge, and obtaining a tissue biopsy [15].

In verifying tissue pathology, cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK20 are low molecular weight cytokeratins found in epithelial neoplasms [16]. Lung carcinomas stain CK7(+) and CK20(-), while intestinal carcinomas are CK20(+) and CK7(-). Caudal type homeobox 2 (CDX2) is a homeobox gene that is highly expressed in primary intestinal adenocarcinomas [17]. The nuclear transcription termination factor (TTF) TTF-1 is highly expressed in lung carcinomas. Napsin A (Nap-A) is a functional aspartic proteinase that is more sensitive than TTF-1 in detecting primary lung NSCLC [18]. Thus, positive immunostaining with TTF-1, CK7, and Napsin A, and negative CDX2 and CK20 markers would indicate that an undifferentiated tumor in the colon is a metastatic lung tumor [19].

In this report we highlight a patient with an established diagnosis of primary NSCLC who underwent right lower lobectomy and subsequently developed an obstructive, ulcerating metastatic lesion in the sigmoid colon two years later. The sigmoid thickening had been visualized on prior CT scans and despite negative biopsy results, the patient’s worsening clinical symptoms and continued growth of the colon mass warranted further investigation and subsequently was diagnosed as a colonic metastasis.

Early detection of lung cancer is critical as early-stage lung cancer is associated with an improved 5-year survival rate. Patients with metastases to the colon tend to have much poorer prognosis due to the disease burden. A high degree of clinical suspicion is imperative in identifying this uncommon form of lung metastasis and to direct appropriate course of management.

- de Groot PM., Wu CC., Carter BW., Munden RF (2018) The epidemiology of lung cancer. Transl Lung Cancer Res 7: 220-233. [Crossref]

- Popper HH (2016) Progression and metastasis of lung cancer. Cancer Metastasis Rev 35: 75-91. [Crossref]

- Kim SY., Ha HK., Park SW (2009) Gastrointestinal Metastasis from Primary Lung Cancer: CT Findings and Clinicopathologic Features. Am J Roentgenol 193: W197-W201. [Crossref]

- Milovanovic IS., Stjepanovic M., Mitrovic D (2017) Distribution patterns of the metastases of the lung carcinoma in relation to histological type of the primary tumor: An autopsy study. Ann Thorac Med 12: 191-198. [Crossref]

- Yamamoto M., Matsuzaki K., Kusumoto H (2002) Gastric metastasis from lung carcinoma. Case report. Hepatogastroenterology 49: 363-365. [Crossref]

- Antler AS., Ough Y., Pitchumoni CS., Davidian M., Thelmo W (1982) Gastrointestinal metastases from malignant tumors of the lung. Cancer 49: 170-172. [Crossref]

- Ryo H., Sakai H., Ikeda T (1996) Gastrointestinal metastasis from lung cancer. Nihon Kyobu Shikkan Gakkai Zasshi 34: 968-972. [Crossref]

- McNeill PM., Wagman LD., Neifeld JP (1987) Small bowel metastases from primary carcinoma of the lung. Cancer 59: 1486-1489. [Crossref]

- Hu Y., Feit N., Huang Y., Xu W., Zheng S., et al. (2018) Gastrointestinal metastasis of primary lung cancer: An analysis of 366 cases. Oncol Lett 15: 9766-9776. [Crossref]

- Boussios S., Pentheroudakis G., Katsanos K., Pavlidis N (2012) Systemic treatment-induced gastrointestinal toxicity: incidence, clinical presentation and management. Ann Gastroenterol 25:106-118. [Crossref]

- Hirasaki S., Suzuki S., Umemura S., Kamei H., Okuda M., et al. (2008) Asymptomatic colonic metastases from primary squamous cell carcinoma of the lung with a positive fecal occult blood test. World J Gastroenterol 14: 5481-5483. [Crossref]

- Kim MS., Kook EH., Ahn SH (2009) Gastrointestinal metastasis of lung cancer with special emphasis on a long-term survivor after operation. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol 135: 297-301. [Crossref]

- Sakai H., Egi H., Hinoi T (2012) Primary lung cancer presenting with metastasis to the colon: a case report. World J Surg Oncol 10: 127. [Crossref]

- Yang CJ., Hwang JJ., Kang WY (2006) Gastro-intestinal metastasis of primary lung carcinoma: clinical presentations and outcome. Lung Cancer Amst Neth 54: 319-323. [Crossref]

- Silvestri GA., Gonzalez AV., Jantz MA (2013) Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: Diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 143: e211S-e250S. [Crossref]

- Chu P., Wu E., Weiss LM (2000) Cytokeratin 7 and cytokeratin 20 expression in epithelial neoplasms: a survey of 435 cases. Mod Pathol Off J U S Can Acad Pathol Inc 13: 962-972. [Crossref]

- Werling RW., Yaziji H., Bacchi CE., Gown AM (2003) CDX2, a highly sensitive and specific marker of adenocarcinomas of intestinal origin: an immunohistochemical survey of 476 primary and metastatic carcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol 27: 303-310. [Crossref]

- Turner BM., Cagle PT., Sainz IM., Fukuoka J., Shen SS., et al. (2012) a new marker for lung adenocarcinoma, is complementary and more sensitive and specific than thyroid transcription factor 1 in the differential diagnosis of primary pulmonary carcinoma: evaluation of 1674 cases by tissue microarray. Arch Pathol Lab Med 136: 163-171. [Crossref]

- Rossi G., Marchioni A., Romagnani E (2007) Primary lung cancer presenting with gastrointestinal tract involvement: clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical features in a series of 18 consecutive cases. J Thorac Oncol Off Publ Int Assoc Study Lung Cancer 2: 115-120. [Crossref]